Strolling Through Spines for Solace and Sobriety

“I’ve been drunk for about a week now, and I thought it might sober me up to sit in a library.’” The man with owl-eyed spectacles, The Great Gatsby.

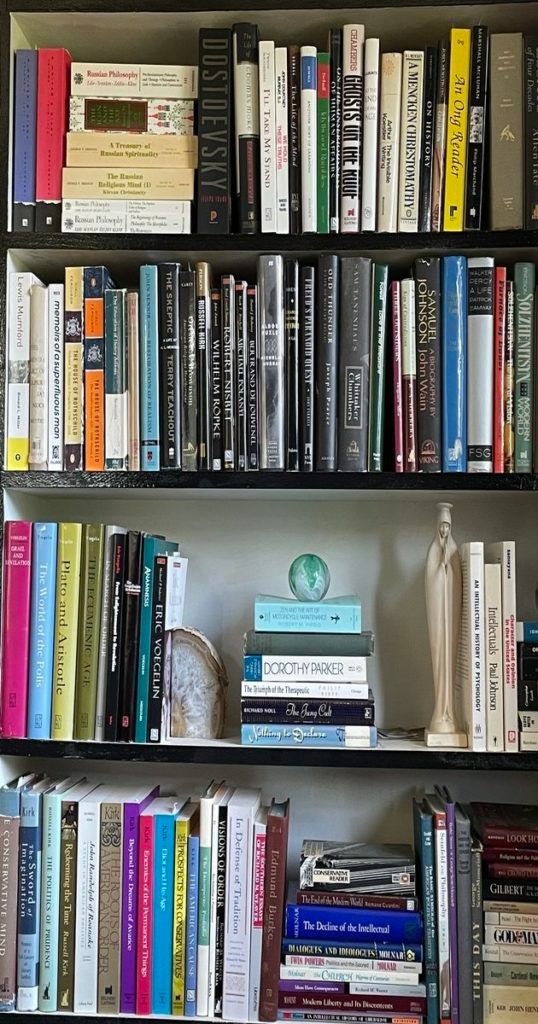

I sit, in a battered, leather chair. It affords me a view of all three ceiling-to-floor bookcases in my study.

My study contains the 1,000 best books from my library. Every one of them is great, though it’s the rare visitor who finds any of them interesting and no one finds them monetarily valuable. I have a first edition Chesterton, which is supposedly worth $75, but otherwise, I’d be lucky to get an average of $1 per book.

I’ve never bought collector editions. On top of that, I’ve bought a fair number of paperbacks. On top of that, I marked up a lot of the books with pen and pencil. And on top of that, the books don’t interest anyone (did I mention the rare visitor?).

But here I sit, looking at them on a Sunday morning, with my whole being bruised and battered by a hard October of travel and incessant small talk, which for me, is roughly the equivalent of a hard October of dog bites and getting slapped in the genitals.

The mere bindings of the books offer solace. I kind of feel like the man in Gatsby’s library, who looks at Gatsby’s books in an effort to sober up. I’m punch drunk from life’s events. Looking at my books sobers me up. Unlike Gatsby, though, who bought the books for display only, I’ve at least cracked the spine on them.

Among the books with cracked spines?

The collection of essays by Whittaker Chambers, Ghosts on the Roof. Was there ever a man more tortured than Chambers? Gay and Communist, in the 1930s. I’m not clear on how or when he stopped being gay, but he married and had a daughter, whose little ear convinced him there must be a God and that the atheism of Communism must be false, and therefore, Communism is false. He converted to Quakerism and fought against Communism, which made the Left loathe him because he knew a lot . . . and a lot of names, like Alger Hiss.

There’s my Russell Kirk collection. The mere mention of “Russell Kirk” soothes me, such was his eccentricity and graceful prose, it makes one feel that we can survive in the world without being a part of it. My daughter Meg is spending a weekend in Mecosta, Michigan in November. I hope she’s able to see Kirk’s ancestral home, which locals have long called “Piety Hill” because of the spiritualist practices and paranormal activity of the place.

Above Kirk, sits the Voegelin collection. If Kirk’s prose is graceful, Voegelin’s is . . . whatever the opposite of “graceful” is. I started reading Voegelin in my twenties, at Kirk’s suggestion in Enemies of the Permanent Things (Kirk’s second-best book). I grew so frustrated at the prose that I called “Information” (555–1212), got Kirk’s home phone number, called him, and asked him to explain what Voegelin was saying in Israel and Revelation. Yeah, I’m an ass, bothering the great man like that, but he came to the phone and talked with me. When I told his widow Annette about it years later, she said, “That was Russell. He was willing to talk to anyone who showed genuine interest” (rough quote).

Fifty biographies sit above the Voegelin collection. If the afterlife really is like Chesterton’s Inn at the End of the World, I hope these guys let me sit at their table occasionally. The Education of Henry Adams, Memoirs of a Superfluous Man (Albert Jay Nock), Chronicles of Wasted Time (Malcolm Muggeridge), and The Autobiography of Malcolm X, who puzzles me greatly, not least because the prose in this modern classic simply isn’t good.

Those are just a few of the autobiographies. Then there are the biographies: Dostoyevsky (such is the majesty of Joseph Frank’s one-volume condensation of his great biography, no subtitle is needed), Pilgrim in the Ruins (Walker Percy), Old Thunder (Hilaire Belloc), The Skeptic (H.L. Mencken), Forgotten Founder, Drunken Prophet (Luther Martin).

That last one is a fun book. Luther Martin is an American founder you never hear about, probably because he loathed centralized government and believed states should be allowed to print their own money. If he were alive today, he’d be a zillionaire: he would’ve bought as much Bitcoin as he could in 2010 at five cents a coin, assuming, of course, he were sober enough to figure out how to set up a digital wallet.

Saint biographies rest above the secular biographies. If I make it to a heavenly afterlife, I’ll be content if a few of these folks deign to glance at me occasionally. Solanus Casey, whose beatification ceremony I attended and, such is the disgraced state of my soul, was one of the worst days of my life. Edith Stein, whose Jewishness doesn’t shame me from telling those jokes. Thomas Merton . . . not remotely a saint, but I think he would’ve come back around if that fan hadn’t electrocuted him. St. Martin of Tours, whose life by Henri Geon might be the greatest saint biography of all time.

And above those saints rests the Inklings: Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. They were truly great men, who wrote popular prose when they weren’t commanding respect from their peers at Oxford University, where some of the greatest minds in history have been gathering since 1100 AD. I feel insignificant and unworthy, just looking up at their books.

That’s a partial tour of the first bookcase. There are two more. The next time life has me bruised and battered, I’ll take a walk through them. This little exercise, by itself, has left me a bit invigorated. If it has amused or otherwise entertained you, I’m doubly invigorated.