How to be a Good Agrarian

I hung out with Michael Jordan outside Chicago about twenty years ago.

No, not basketball Michael Jordan. I'm talking about Michael Jordan, the English professor from Hillsdale College.

We met at a Touchstone conference at Mundelein Seminary. He saw my name tag and said he enjoyed my articles. Being a narcissist, I was smitten, and we talked a bit and took a few meals together. Because we only lived an hour apart, we kept in touch for awhile and met for lunch once, but then drifted away into life.

I bumped into him a few months ago at a Hillsdale cross-country meet. He had just retired due to some health problems. We caught up a bit and I haven't seen him since.

And then yesterday, I read (what I think is) a farewell essay to Hillsdale alumni. It's a pithy, fast-paced piece: beautiful in its simplicity, wise in its advice.

Unfortunately, I couldn't find a link. Maybe he'll see this post and send me a link or the entire article.

For today, though, here are a few of my favorites from his “How to be a Good Agrarian in the 21st Century.”

- Be a member of your community, not a mere consumer in the global economy.

- Be as self-resilient you can be in terms of home economics and home culture.

- The food you raise yourself will be better tasting, more nutritious, and healthier than what you find at the supermarket.

- Try to avoid specialization and the division of labor: When you can, be your own doctor, plumber, carpenter, painter, etc.

- “Throw out the radio and take down the fiddle from the wall.” Quoting Andrew Lytle from the excellent I'll Take My Stand.

- Settle in a particular place, ideally the place where you were born and where your extended family lives.

- Every few years read The Memory of Old Jack, Hard Times, and other agrarian writings to remind yourself how you ought to live and work, and how you ought not to live and work.

The Full Agrarian Letter

After I published the foregoing, Professor Jordan saw it and see me his full agrarian letter for publication here:

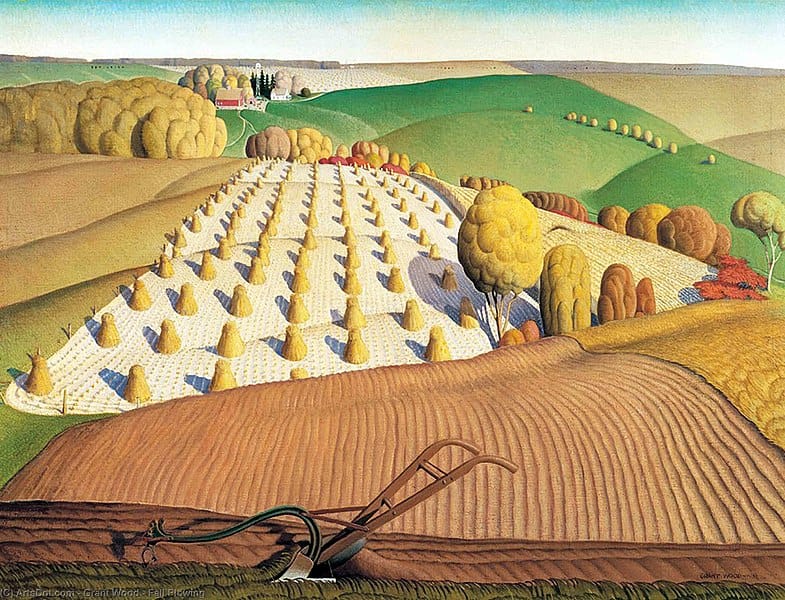

While it is unlikely that you will take up the plow after you graduate, you can still be a good Agrarian. Here are a few Agrarian admonitions that direct us toward what is called the American Dream, what we might also call the Good Life.

Whenever possible, show loyalty and solidarity with your community by shopping at the small shops: at locally owned and locally managed businesses, places where you might encounter the same face behind the counter over a period of years. Be a member of your community, not homo economicus, a mere consumer in the global economy. In G. K. Chesterton’s The Outline of Sanity (section two on “Some Aspects of Big Business”), Chesterton argues (and demonstrates) that the small shops are often better than the large stores from both the moral and the mercantile points of view.

Remember Wordsworth’s sonnet; avoid the fate of men devoted to utility and consumerism:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and Spending, we lay waste our powers:

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

Put the interest of God, community, and family before self-interest. This is perhaps more a Christian admonition than an Agrarian, though it is implicit (and sometimes explicit) in some of the “Agrarian” writings we’ve examined. The admonition has bearing on your life in this world and, if Jesus is correct, in the life to come.

Be as self-reliant as you can be in terms of home economics and home culture.

Whenever you can, be your own farmer. Keep bees and make maple syrup; raise vegetables, flowers, fruit trees and vines. Live where you will be permitted to raise fowl — for eggs and meat. If you get especially “agrarianous,” you could raise larger animals: pigs, goats, and beef and milk cows.

Remember Hesiod’s advice to his lazy brother Perses: “First of all, get yourself an ox for plowing, and a woman– / For work, not to marry — one who can plow with the oxen.” My own advice is that you find a spouse (a wife or husband) for marriage and for work, someone who loves you and who likes to be economically and culturally self-reliant. Remember Jack Beechum’s tragic fate in Berry’s The Memory of Old Jack: while he did enjoy “the yeoman’s tradition of sufficiency to himself, of faithfulness to his place,” he did “not unite farm and household and marriage bed.”

The food you raise for yourself and your family will be better tasting, more nutritious, and healthier than what you find at your local supermarket. If you don’t raise your own vegetables and grow your own meat, endeavor to get them from a local source.

Extend this self-reliance to other areas of the home economy: when you can, be your own doctor (practice home medicine), your own plumber, carpenter, painter, etc. In other words, endeavor to avoid specialization, the division of labor, by being well-rounded. Teach your children (if you are blessed with them) at home; teach them both religion and academics at home, by precept and by example. Do this even if you send your children to Sunday school and public or private schools.

As for self-reliance and home culture, take to heart Andrew Lytle’s admonition in the Agrarian Manifesto I’ll Take My Stand: “Throw out the radio and take down the fiddle from the wall. Forsake the movies for the play-parties and the square dances.” Let your home culture be a way of life and not a commodity, not a commercial enterprise or expense. Ideally, this home culture should grow out of the traditions of a particular people living in a particular place; it should be both traditional and organic, not imported from outside the region. As John Crowe Ransom observes in the Agrarian Manifesto, cultural poverty cannot be cured “by pouring in soft materials from the top.” Here we’re talking about folk arts and crafts, which thrive best in traditional agrarian communities. But if the folk arts are not to your liking, and you prefer instead “highbrow” art, well and good. But endeavor to enjoy this highbrow art as a participant, not as a mere spectator. In other words, take the violin out of its case, and play Mozart and Vivaldi.

Settle in a particular place, ideally the place you were born and where your extended family lives. There immerse yourself in both family and community life. If you can, avoid the large cities. Think of Jefferson’s denunciation of cities and mobs; think of Luke in Wordsworth’s “Michael.”

Cultivate good stewardship of natural resources and practice piety toward Creation. Virgil’s Georgics and Ruskin’s essays, among other semester readings, stress these points. Remember that utility, beauty, and morality can and should be combined in life and work, in culture and art. Pope’s “Epistle IV. To Richard Boyle, Earl of Burlington” and Ruskin’s essays remind us of this.

If you do become the CEO of a large corporation, or a banker, don’t be a Bounderby. In whatever career you make for yourself, remember the Golden Rule and the second Great Commandment. Remember the first Great Commandment as well.

If you become a teacher, don’t be a Gradgrind. Cultivate both the hearts and the minds of your students. And don’t forget the body, either.

Every few years read The Memory of Old Jack, Hard Times, and some of the other “Agrarian” writings we examined this semester–to remind yourself how you ought to live and work, and how you ought not to live and work. This will help you to be a good Agrarian, or better yet, a worthy steward, a humane person.

Have a blessed Christmas and a wonderful life.