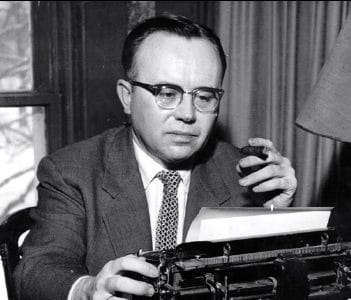

Russell Kirk: The Anti-Modernist Cerberus

The author of The Conservative Mind opposed modernity in at least three ways

Russell Kirk hated modernity.

He rebelled against it his entire life. He hated the automobile, calling it a “modern Jacobin.” He wouldn't allow a TV in his house (though he let a hobo named “Clinton” have one in his room), and once, when he found out his daughter was watching TV, hurled the set from a third-floor window. Bradley Birzer, Russell Kirk: American Conservative, 521.

He didn't even like the radio, sharing his friend, Max Picard's, intense dislike for “radio noise.”

But what exactly is “modernity”?

Thinkers quibble over its meaning, but I think most would agree that it was given form by the Enlightenment, reveres science, and is marked by a vague sense that the human race will have continual success in its worldly activities . . . through the exercise of reason.

Many people refer to modernity as “The Age of Reason.”

Others point out that it's marked by “Rationalism.”

Kirk would've agreed.

He countered that “rationalism” is merely “defecated rationality.” Kirk, Beyond the Dreams of Avarice, “Liberal Learning, Moral Worth, and Defecated Rationality,” 153.

But his dislike of modernity and its exclusive use (worship) of reason didn't stop with funny slurs and personal idiosyncrasies. He opposed it in at least three ways:

First, he wrote The Conservative Mind and gave the whole conservative philosophical tradition a name. Prior to Kirk, no one quite knew what to call that gaggle of writers, thinkers, and politicians who battled against the rational mindset of modernity. By giving it a name and a pedigree, he gave it respect.

Second, he converted to Catholicism, albeit a bit later in life. The Church is inherently anti-modernist. It is bigger than all cultures and eras, so it can thrive in any culture or era, but it has struggled with modernity for a host of reasons that go way past this piece. I'm not the first one to note that many medieval thinkers have much in common with atheistic postmodernist thinkers.

Third, Kirk was an occultist, of sorts. The occult is a celebration of the irrational and Kirk reveled in it his entire life, from seeing ghosts to writing about the paranormal.

It's the Halloween season, so I'll just leave you with a handful of quotes and anecdotes from Birzer's magisterial biography to illustrate this third head of Kirk's opposition to the rationalism of modernity:

As a child, he had seen two ghostly figures staring at him from outside in a blizzard. The taller one, wearing a beard, was Dr. Cady. The shorter, wearing a turban, was Patti. Kirk's aunt Fay had encountered the same figures as a little girl, and they showed themselves to Kirk's daughter Monica as well.

Kirk delved deeply into and read extensively in the serious literature about the supernatural and the occult.

[He] contributed to at least one serious work of the occult, Stranger Powers of ESP (1969) by Brad Steiger.

As a graduate student in Scotland, Kirk saw fairies, goblins, and several ghosts.

From one of his letters while living in Scotland: “Tomorrow will be Halloween – and no better place for it than St. Andrews. The Scots make a great event of it. I shall keep an eye out for ghosts in the Pends.”

From another letter while living in Scotland: “The ghosts have been lively of late. There are strong men who refuse to frequent certain parts of the town about the cathedral ruins o'nights. The ghost in my room is allegedly a “dear, sweet old lady,” but though I am willing to concede she is incredibly old, I suspect that she is neither dear nor sweet. Last night at four, she stumbled about my chamber like a soul most literally lost, knocked down a book from my table, and laid a hand upon my hand–hers outside the blanket, mine inside. I refused to grant her the satisfaction of chilling my blood with her icy glare, and kept my head well under the covers until I drifted back to sleep.”

In the 1960s, the Count Dracula Society, located in southern California, named him a knight of the organization, and Kirk proudly maintained his involvement in the society for a considerable period of time.

As late as 1973 . . . he continued to read the tarot cards for guests, and he maintained his love of Halloween – “an annual occasion of dreadful joy at my house” – to the end of his life. “Kirk was [an] old hand at telling fortunes by the Tarot, long before the art was taken up by hippies,” he wrote of himself in a publicity brochure.

In an age of scientism, the rational person and the culture dismissed the supernatural event as ridiculous and religion as a whole as superstitious. But, as Kirk put it rather humorously, the haunting and haunted spirits of the world in turn “simply ignore rationalists.”

Kirk believed that his ancestors haunted Piety Hill until the great fire destroyed it all on Ash Wednesday in 1975. (Piety Hill was his home in Mecosta, Michigan. I stayed there one night, a guest of Annette Kirk's. Kirk said that, although he didn't see ghosts after 1975, he continued to hear strange noises at night. I can't say I heard anything, but I'd had quite a few glasses of wine when I laid down.)