Is the New Left the Old Occult?

The supernatural and paranormal. Postmodernism and critical theory. What could be the connection?

Over 40 years ago, Norman Cohn, author of that masterpiece about countercultural movements in the Middle Ages, The Pursuit of the Millennium, wrote a review about a little-known book by a young genius who would commit suicide at age 34.

The author: James Webb, a graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge, a man who Colin Wilson considered “one of the most brilliant minds of his generation.”

The book: The Occult Establishment (1976).

Cohn said:

[T]his book performs an important task. It offers the most vivid portrayal yet given of that hydra, irrationalism; and leaves one waiting, with curiosity if not with trepidation, to see what the next head will look like. “In Pursuit of the Irrational,” The Times Literary Supplement, June 17, 1977.

The Occult Establishment is now out of print. Amazon says my copy is worth $100, if only I hadn’t beat the hell out of it with my underlinings and side notes.

But I didn’t know it would go out of print, and I didn’t know Webb was a genius of the first order.

Besides, I probably couldn’t have helped myself anyway.

The book is packed with fascinating (underline-worthy) facts about the 20th-century occult.

What is the Occult?

The “occult” is an umbrella term. It means anything pertaining to the mystical, supernatural, magical, and paranormal that falls outside religion or science.

Both religion and science use reason and logic to construct their “systems.”

The occult, on the other hand, embraces the irrational.

Religion and science seek to explain, but the occult revels in the unexplainable.

The occult, in fact, could be, and has been, defined as “rejected knowledge”: the knowledge rejected by the establishments of religion and science (OE, 15).

The term is so loose and all-embracing that it can be made to cover Spiritualism, Theosophy, countless Eastern (and not so Eastern) cults; varieties of Christian sectarianism and esoteric pursuits of magic, alchemy and astrology; also the pseudo-sciences such as Baron Reichenbach’s Odic Force or the screens invented by Dr. Walter Kilner for seeing the human aura. OE, 15

The Occult Establishment looked at occult activity in the 20th century. It was a follow-up to Webb’s The Occult Underground, which examined the rise of the occult in the 19th century.

The occult, Webb said, rose in the 1800s in opposition to the Enlightenment and rationalism. It then grew and, in the 1900s, became organized.

And political.

Webb documents in The Occult Establishment that, as the occult grew stronger in the 20th century, it started to take political positions. The entire book paints pictures of those political movements, from Nazism to the Haight-Ashbury and Jerry Rubin’s “Be-In.” He calls them the “Progressive Underground” (as opposed to the 19th-century’s “Occult Underground”).

It’s a compelling and fascinating book, but is it relevant today?

The Progressive Underground has disappeared, hasn’t it?

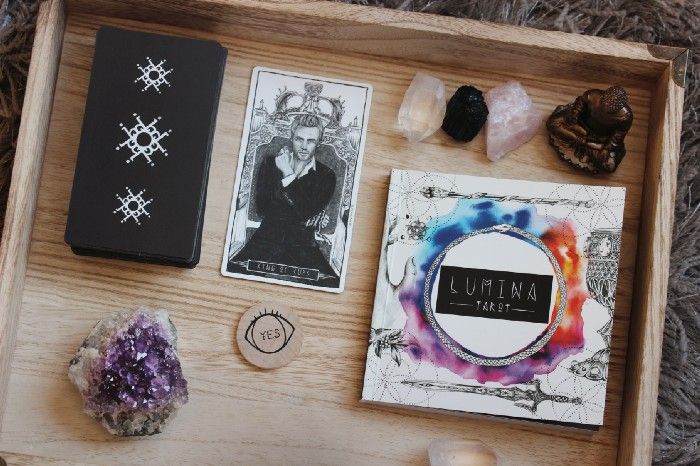

The world today is all about business and technology and aggressive politics. Tarot card readers are derisible oddities and no one is dropping acid as a political statement (Joe Rogan’s efforts to normalize psychedelics notwithstanding). There seems to be an increased interest in UFOs, but it’s based on logical deductions made from increasing video footage.

Go back and look at that Norman Cohn quote above. He said Webb’s book “offers the most vivid portrayal yet given of that hydra, irrationalism; and leaves one waiting, with curiosity if not with trepidation, to see what the next head will look like.”

I don’t know if Cohn knew it, but that hydra’s head was already sprouting in 1977.

It was sprouting under the name of “postmodernism.” The theories of Jacque Derrida and Michel Foucault were a celebration of the irrational. They were an explicit denunciation of the Enlightenment and the rationalism that defined all of modernity. Hence, the name “postmodernism.”

In that sense, the postmodernists were kind of like the 19th-century occultists: a revolt against rationalism, but isolated and not effectively political.

One of the accusations against Derrida, after all, was that his theories merely tore down modernity but didn’t offer any political options, which made him irrelevant. Mikics, Who Was Jacques Derrida? 217.

Thaddeus Russell strenuously argues that Foucault’s theories aren’t political (though Foucault himself was; he, for instance, manned barricades and threw rocks at police during the 1969 “battle of Vincennes.” Miller, The Passion of Michel Foucault, 178). If anything, Russell appears to argue, the upshots of Foucault’s theories are libertarian (which, among political theories, is the most “a-political” . . . it’s the politics of being left alone).

Derrida’s and Foucault’s theories, in other words, were attacks on the Enlightenment and rationality, but they weren’t political.

Enter critical theory

At the same time that postmodernism was developing under Derrida and Foucault, critical theory was developing.

Critical theory is Marxist.

And for the Marxist, it’s all politics, all the time.

Combined, critical theory and postmodernism picked up the same torch Webb described in The Occult Establishment: progressive politics under the banner of the irrational. Postmodernism tore down the rational systems of the Enlightenment. Critical theory then purported to come into the rubble and take control of society through politics.

Postmodernism, you might say, got the land ready. Critical theory planted in it.

Postmodernism was parallel to the 19th-century Occult Underground. Critical theory was parallel to the 20th-century Progressive Underground.

If Webb had written about this hydra head in anti-Enlightenment/anti-rationalism history, postmodernism might be the subject of the Occult Underground book and critical theory might be the subject of the Occult Establishment book.

Social Justice: A new religion or the old occult?

Enter Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay and their 2020 book, Cynical Theories.

They explain the rise of postmodernism and how it combined with critical theory to create the highly-political climate we’re in today. They claim that postmodern/critical theory has become a type of religion under the name “Social Justice” with the “firm conviction associated with religious adherence.” Cynical Theories, 18.

Now, Pluckrose and Lindsay are atheists. To the atheist, anything that isn’t physical and verifiable empirically falls into the bucket of religion. Superstition, prayer, the Mass, tarot cards: they’re all the same thing.

Atheists don’t tend to distinguish between religion and the occult. Webb said “occult” means all forms of knowledge that aren’t religious or scientific. To folks like Pluckrose and Lindsay, “religion” means all forms of knowledge (or imagined knowledge) that isn’t scientific.

I think Lindsay and Pluckrose should take a harder look at the occult and see how it differs from religion.

They could start with the most fundamental difference: religion doesn’t seek control, whereas the occult is all about control.

Or they could focus on reason and science: Religion doesn’t reject science and it doesn’t reject reason. The occult rejects both.

And so does the New Left. Its adherents, for instance, have declared that math is part of the white supremacist patriarchy and science is just a societal construct.

I’d respectfully submit that the rise of the deconstructionist, postmodern, critical theory Left is the newest head of the hydra irrationalism that Norman Cohn referenced.

And if we start looking at the New Left through those glasses, especially as focused by James Webb’s two great works, we’d understand it more clearly.

Further reading

Worth noting: McGilchrist points out that the "uncanny" (irrational perceptions) arose in the immediate wake of the Enlightenment. The left hemisphere's excessive rationalism, McGilchrist speculates, led the right hemisphere to rebel in an odd way.

Just as I believe the right hemisphere has been rebelling ever since the Great Rejection.