Parliament Created the Great London Gin Craze

“[N]oe sort of Brandy Aqua vite or other Spirits or distilled Waters of any Kingdome Country or place whatsoever shall after the said foure and twentyeth day of August be imported into the Kingdoms of England or Ireland . . .”.

If you read the Wikipedia entries about England’s Great Gin Craze, you see descriptions about how bad it was and how Parliament passed a series of acts to stop it.

But you see scarcely any references to the series of Parliamentary Acts that caused it in the first place.

Let’s look at England at the end of the 17th century.

It had a new royal family in the form of William of Orange, who usurped James II’s throne in the 1688 Glorious Revolution.

William was not universally liked, especially among the Jacobites, who never stopped scheming to get James Stuart II back on the throne.

William was also not liked by the French, whom he bitterly fought in the War of the Grand Alliance and who worked with the Jacobites to get the Stuarts back on the throne.

William, in turn, hated the French and so did his supporters in Parliament.

What better way to strike at the French than to ban trade with them, including a prohibition on its brandy? And so that’s what happened, almost immediately after taking the throne by the passage of the Trade with France Act of 1688, which took specific aim at French brandy (the most popular liquor in England at the time).

“The Howards . . . the Cavendishes, the Cecils, the Russells, and fifty other new families . . . rose upon the ruins of religion.” Hilaire Belloc, The Servile State.

At the same time, Parliament passed the Distilling Act of 1690 that authorized anybody to distill spirits. This created a heavy demand for grain, which drove up the price and assured that the farmers would never be stuck with a surplus.

As a result, the Distilling Act greatly increased the value of farmland, which was controlled by the great families that received huge swaths of land in Henry VIII’s attack on the Roman Catholic Church and, especially, its monasteries.

Parliament then passed the 1694 Tonnage Act, which imposed a heavy tax on beer. The result? Gin became the cheapest alcohol drink in England.

And then, in 1720, Parliament passed the Mutiny Act, which exempted distillers from the requirement to accept billeted troops. Every father who didn’t want soldiers living in his house with his wife and daughters became keenly motivated to start making gin.

Here’s the thing: England was ripe for a “geneva” revolution no matter what.

Prior to 1688, gin was primarily considered medicinal.

But with William and Mary’s ascension, the juniper drink from the Protestant Lowlands became the drink of royalty. It quickly became fashionable, especially since, due to ongoing hostilities with the French, it was no longer fashionable to drink brandy.

Gin was also cheap to produce.

Gin didn’t need parliamentary encouragement anymore than today’s marijuana industry needs legislation to encourage the cultivation and enjoyment of marijuana.

Yet that’s what Parliament did.

And the result was one of the worse self-induced public health spectacles in English history.

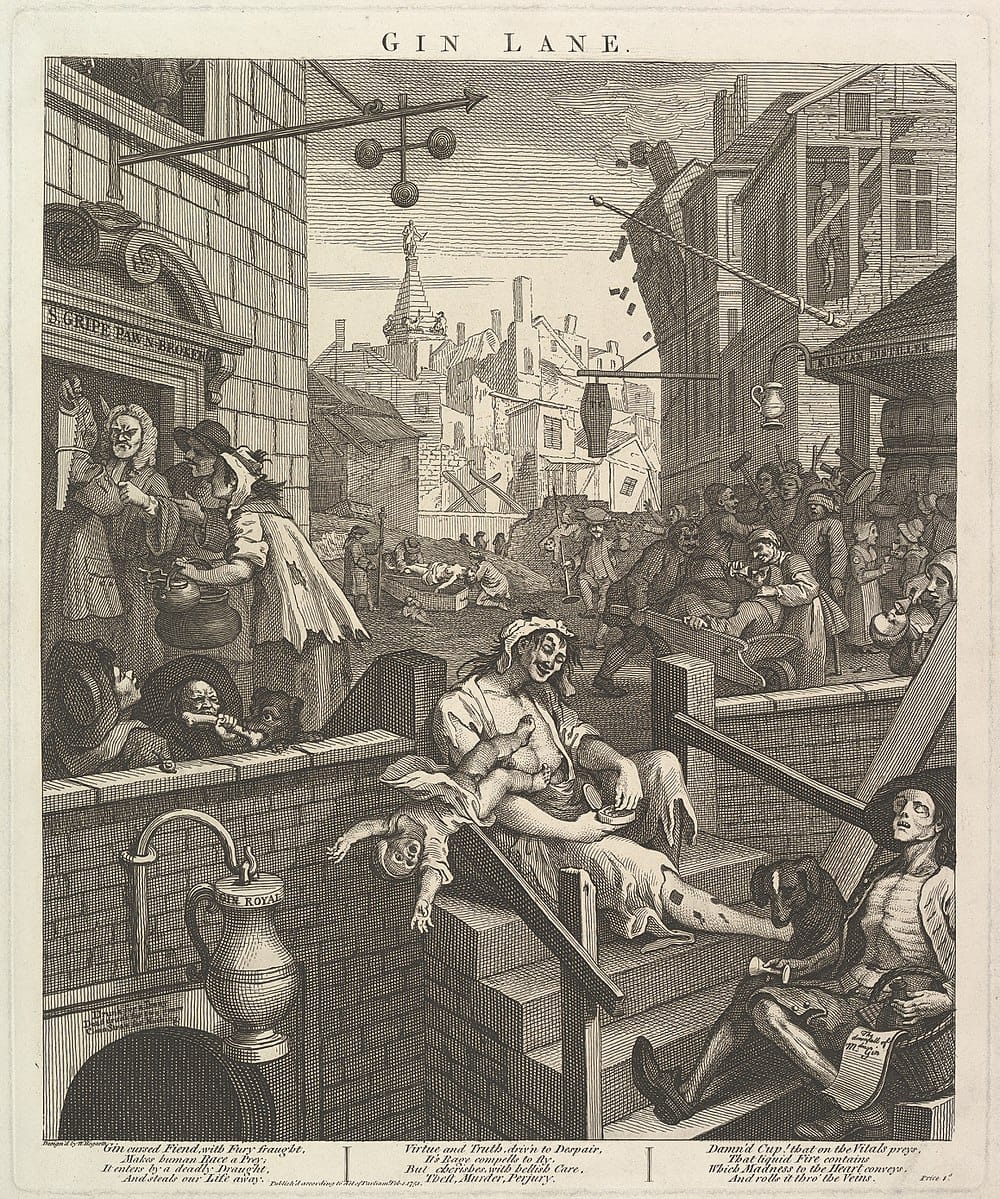

The Great Gin Craze that racked England after 1720 was awful.

Gin was everywhere. Much of it was “cut” with turpentine or sulfuric acid to dampen the juniper taste and was sold out of wheelbarrows, alleys, backrooms, and cheap lodging houses.

There were 8,659 gin shops in London alone, according to William Maitland.

Men and women died in the gutters after drinking too much, which was better than others who simply dropped dead on the spot where they were drinking. Londoners saw people staggering blindly day and night. Fights were frequent. Fire outbreaks from neglect were common. Children gathered in the gin shops and would drink until they couldn’t move. Drunk mothers neglected their babies. Girls as young as 13 sold themselves for gin. The hospitals were seeing increasing numbers of gin-related illnesses, including malnourished babies.

Parliament responded, passing the 1736 Gin Act, which imposed a duty of 20 shillings per gallon of gin and required retailers to purchase an annual license. The Act proved impossible to enforce.

Parliament would then introduce additional legislation with similar lackluster effect, until 1751’s Gin Act, after which the problem started to subside.

So perhaps we can give Parliament a little bit of applause for fixing a problem it caused in the first place?

Probably not. Many historians think the rise of tea and the revival of Methodism that took hold of England at this time is far more responsible than any of the Gin Acts.