From the Notebooks

20th Century Existentialism

Four subjects that were wildly popular in the 20th century:

Zen arose when Mahayana Buddhism merged with Taoism. Buddhism is steeped in a thing called “monism,” which teaches that all things are one. Individual things don't exist; individual classes of things don't exist. There is, in other words, no essence at all. In this, Zen might be the most radical form of existentialism. Its techniques–whether quiet meditation or sudden enlightenment or koans–are all designed to get its practitioners beyond “subject-object” . . . beyond the separateness of all things and beyond all essence.

Jack Kerouac dripped Buddhism. He practiced dhyana, Buddhist meditation. He at times took vows to lead a Buddhist life. In one vow, he promised to limit his sexual activity to masturbation (apparently his idea of austerity), another time he vowed to eat only one meal per day and to write about nothing but Buddhism. He at times exclaimed, “I am Buddha,” and once asked the modern Zen master D.T. Suzuki if he could spend the rest of his life with him. His On the Road is a portrait of a young man with zero concerns about essence-filled societal conventions.

J.D. Salinger's Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye punches and weaves through everyday banalities that most people embrace. He disdains the ballyhooed elite prep school he attends; he thinks little of money; he is nauseated by the forms of entertainment most people find enjoyable. He intuitively sees the shallowness of the things that are the cheap fodder of existence for most people. Holden is merely a watered-down, less radical, version of Mersault. Both are existentialist characters that pull away from a society that is filled with essences, accidents, and definitions . . . things that Holden finds confining and Mersault doesn't even condescend to acknowledge. Salinger would expand this theme in Franny and Zooey.

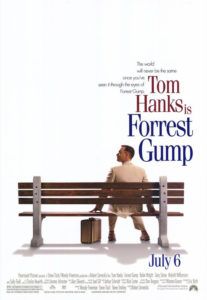

The movie Forrest Gump is a 142-minute lesson in how a man with an IQ of 75 can make it in a world . . . if he is an existentialist. Intelligence is needed to navigate the world of essence and definitions: to be clever, to manipulate, to plan, to scheme. None of that is for Forrest. He simply exists. He never even tries to marry or win over his beloved Jenny, but rather, simply accepts her as his “all,” with no reference to himself.