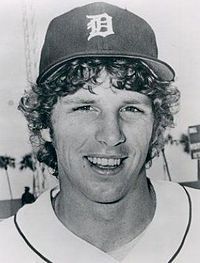

The Bird

On Mark Fidrych

On days like that, you didn't dare drink too much beer in old Tiger Stadium. The place was packed and its limited bathroom facilities meant you missed two innings every time you needed to make a run.

It was 1976, and the Tigers were horrible. The year before, they had the worst record in the Major Leagues: 57-102. They didn't have a single legitimate all-star player in 1975, but the leagues were required to invite a player from each team, so the Tigers' aging catcher, Bill Freehan, was invited out of respect for his stellar play in earlier years. By the next year, he wasn't even the Tigers primary catcher anymore. That duty went to Bruce Kimm, who was catching on this packed day to Mark “The Bird” Fidrych.

I don't remember anything about that 1976 game, except it was hot and the place was packed. I don't know if we won or lost. I just waited for The Bird to get back on the mound, then I watched him through my binoculars the entire time.

I don't remember how my brother (a college kid with no money) scored the tickets, but when he told me we were going, I was excited: To this ten-year-old, the Tigers were everything during the summer. I heard stories about 1968 (I was only two during the Year of the Tiger). I sulked through 1975, wishing Al Kaline or someone would emerge to take the Tigers back to the top.

Instead of Kaline, we got a freak show.

Most people know about The Bird: He smoothed the mound with his hands, talked to the ball, jumped around the infield. He was bizarre, but also a great pitcher.

He didn't elevate the Tigers to great things. They finished second-to-last in their division with a 74-87 record. That was considerably better than 1975, but it wasn't until the following year, with the arrival of Alan Trammel and Lou Whitaker, that the Tigers would begin their ascent in the AL East that culminated in their high-octane 1984 team.

Fidrych didn't share in that team glory. He tore a cartilage in his knee in early 1977, then hurt his shoulder. He finished the season 6-4. Doctors failed to diagnose that his hurt shoulder was a rotator cuff tear. By the time it was operated upon in 1985, The Bird was finished as a ball player.

He spent the rest of his life back home in Massachusetts. He owned a 100-acre farm and a small trucking company. I don't know if he needed much money. He worked for the MLB minimum wage in 1976 ($16,500), but the Tigers gave him a $25,000 bonus at the end of the season and then signed him to a three-year contract worth $225,000.

A few years ago, he died while working on one of his vehicles. He was underneath it. Apparently, his clothes got tangled in the power shaft and he suffocated. He was only 54, which made him way too young to die (I am 54 now).

What do we learn from someone like Fidrych? Life is short and fame even shorter? Strike when the iron is hot? Life is a freak show, but death is for everybody?

Those are possible lessons, but I like this one: Black Swans come in all shapes and sizes.

A Black Swan, according to Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his 2007 bestseller, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, is an event that is rare, has a huge impact in its field, and is retrospectively predictable. Black Swans, Taleb persuasively argues, are all around us. Life isn't largely one of skill, it's largely one of luck.

Fidrych had a meteoric ascent to the top of the biggest pyramid: the sports and entertainment industry in the United States. His ascent was a Black Swan. It was huge, no one expected it, and in retrospect, it was predictable: the guy was a great pitcher (threw 93 mph) with bizarre antics.

But Fidrych didn't just have good luck. He had the bad kind, too: the collapse. The decline was huge, no one expected it, and in retrospect, it was predictable: he pitched a lot. In his Magic Year, he threw consecutive 11-inning complete games, started 13 games on three days rest, and threw 24 complete games (only one fewer than Andy Pettitte has thrown his entire year). He wore out quickly.

In retrospect, I'm not even sure I'd say he had a Black Swann-ish 1976. The first half of the season was a Black Swan: 9-1 at the All-Star break. But he finished 19-9, going 10-8 in the second half of the season. That's not freakishly good or rare, but then again, I think the reduced success was due to a lack of support from Tiger hitters than ability. Fidrych finished 1976 with a low 2.34 and the American League Rookie of the Year Award.

It doesn't really matter now. The man is dead. The Bird took his final swan dive. All that stuff–the ascent and descent and their media trappings–is now washed away for The Bird. The only thing worth contemplating: Is he now making The Real Ascent?

When I heard about his death over ten years ago, I said a Hail Mary for his departed soul. It was the least I could do for all the enjoyment he gave this ten-year-old boy over thirty years ago.