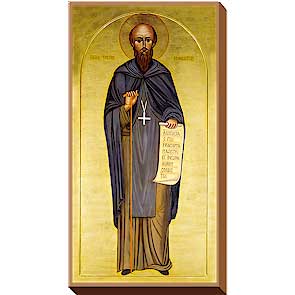

St. Benedict

Today's one of my favorite commemorations: St. Benedict (the First, of Nursia). Why is Benedict important? Lots of reasons, most of which are summed up in this excerpt from an essay I wrote earlier:

When, after 312 and Constantine's conversion, society became comfortable for Christians and a source of temptation, tens of thousands opted for the white martyrdom of the desert.

The exodus to the desert actually started in the mid-third century. St. Jerome said the first solitary ascetic was Paul the Hermit, but most give that honor to St. Antony the Great. In 285, he fled to the wastes of Egypt, there to live by himself in an old empty fort. He stayed there nearly 75 years, coming out only twice. The rest of the time, he stayed there and cultivated intense holiness.

Many people flocked to see this holy man and follow his example. He organized them into loose groups and placed them in separate and scattered cells, instructing them to come together only for common worship. A little later, a man named Pachomius organized these groups into formal monasteries.

From Antony's and Pachomius' beginnings in upper Egypt, the monastic ideal spread to Palestine and Europe. Many of the greatest saints of the age pushed this counter-cultural ideal: Athanasius, Jerome, Basil, Martin of Tours, John Cassian, and, finally, Benedict, who founded his monastery at Monte Cassino (southern Italy) in 529 and wrote his Rule for Monasteries, an ingenious little book that deflated the excessive asceticism that could be found in a few monasteries, struck a healthy alliance of manual and intellectual labor, and demanded three vows: poverty, obedience, stability. He hit the perfect chord, making monasticism much more appealing. The Rule spread and new monasteries sprung up throughout Europe.

These monasteries later preserved the great works of classical civilization from the harsh times that followed the distintegration of the old Roman Empire, the “Dark Ages.”

Rome fell in the 400s, though it didn't “fall” as much as it started to evolve from a centralized state into many smaller “states” ruled by the descendants of the former Roman senatorial class and, more so, Roman army generals–most of which came from barbarian stock. Much of the same social and economic norms that governed the late Roman empire prevailed well into the seventh century.

But the Dark Ages definitely started to set in after the commonly-accepted (even if somewhat erroneous) date of 476, the year the Ostrogroths conquered Rome and installed their king, Odoacer, on the imperial throne. The roads weren't as safe, communications broke down, no one knew for sure who was in charge. Culture and society started to disintegrate.

Things got real rough in the ninth century. Without the monasteries, much of the great works of classical civilization would have been lost. Ironically, these institutions started as an effort to flee the death rattles of a decadent civilization, yet these institutions would preserve that same civilization's great works of art, poetry, drama, philosophy, and science.

Zmirak and Matychowiak cover this feast day in their enjoyable The Bad Catholic's Guide to Good Living. Excerpt:

Western monastic houses inspired by Benedict's Rule . . . created a wide variety of beers, wines, and liqueurs will still enjoy today: Riesling, Trollinger, Scottish Ale, Belgian Trappist Ale, Benedicting, and the sublime Chartreuse, among many others. Without St. Benedict, we would indeed live in a different America today--one in which no one read the classics of ancient literature, understood Latin or archaic Greek, prayed the liturgical hours, fasted for Lent, or drank Chimay with dinner.