Six Challenging Assertions from D. H. Lawrence's Studies in Classic American Literature

Highlightings of D. H. Lawrence's Studies in Classic American Literature

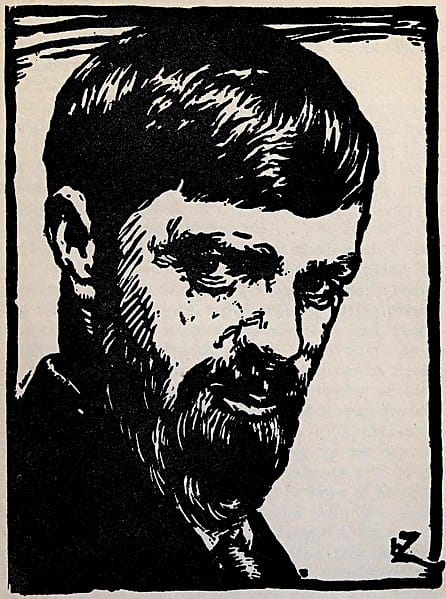

In his Student's Guide to U.S. History, Wilfred M. McClay assembled a list of 26 books and called them “An American Canon.” I was acquainted with most of them (The Federalist, Moby Dick, etc.), but four were new to me, including D.H. Lawrence's Studies in Classic American Literature. “What,” I wondered, "does that British pornographer have to say about American literature?”

For decades I've subscribed to an important corollary of the principle of connaturality: distorted living creates distorted thinking. If a person's life is ruled by passion, his thinking will be distorted by passion. It's no coincidence that sexually-illicit heterosexuals are more likely to support homosexual marriage. For the sexually illicit, sex is king . . . or at least a queen (and maybe a bishop, if you're Episcopalian). They don't think clearly about sex because they're ruled by sex. People think college professors make students into liberals. Maybe, but the students' distorted living plays a heavy role, too.

So I didn't think the Chatterley dude would have a whole lot to say about the United States, especially since he was from Britain.

I was wrong. His book is strong, filled with wise and novel (and funny . . . bonus) observations, like this: “But to try to know any living being is to try to suck the life out of that being. . . It is the temptation of a vampire fiend.” He says some stupid things, too, but he makes many observations about American life that rank with de Tocqueville's Democracy in America, Chesterton's What I Saw in America, and Santayana's Character and Opinion in the United States.

Natural superiority, natural inferiority

When America set out to destroy Kings and Lords and Masters, and the whole paraphernalia of European superiority, it pushed a pin right through its own body, and on that pin it still flaps and buzzes and twists in misery. The pin of democratic equality. Freedom.

There'll never be any life in America till you pull the pin out and admit natural inequality. Natural superiority, natural inferiority. Till such time, Americans just buzz around like various sorts of propellers, pinned down by their freedom and equality.

Political equality, yes. Divine equality, yes. Social, intellectual, physical equality, no.

Yet in America, all things–pursuits and interests, opinions and choices–are deemed equal and deserving of respect. The results are often grotesque (NASCAR nation comes immediately to mind).

Disintegration brings death . . . and life

Lawrence isn't beyond the metaphysical, even when he expresses it in the biological:

The central law of all organic life is that each organism is intrinsically isolate and single in itself.

The moment is isolation breaks down . . . death sets in.

This is true of every individual organism, from man to amoeba.

But the secondary law of all organic life is that each organism only lives through contact with other matter, assimilation, and contact with other life, which means assimilation of new vibrations, non-material. Each individual organism is vivified by intimate contact with fellow organisms: up to a certain point.

In order to have contact with another, we must break down a little, we must lessen our isolation. But if we break down too much, I think Lawrence is saying, we die.

Death results from termination of isolation, yes, but the termination of isolation is necessary for ultimate communion, which, it seems to me, is the logical extension of what Lawrence is saying: A breakdown of isolation is necessary for important communion with others to take place. Likewise, a complete breakdown of isolation is necessary for final communion with The Other to take place.

The root of all evil is . . . the spirit?

Lawrence believes in the spirit. He even understands it, albeit in a warped way:

The root of all evil is that we want this spiritual gratification, this flow, this apparent heightening of life, this knowledge, this valley of many-coloured grass, even grass and light prismatically decomposed, giving ecstasy. We want all this without resistance. We want it continually. And this is the root of all evil in us.

Well, yes, but that yearning is also the root of all good. That desire for spiritual gratification is nothing less than the summum bonum, the final call, our ultimate destiny. When that divine signal gets distorted, troubles arise. Men seek that spiritual gratification in warped ways, from drugs to love of the malevolent. The desire to seek itself, though, is not the root of all evil. It's the desire when distorted by Original–and subsequent Actual–Sin that brings about the evil.

Living without souls

“[P]eople may go on, keep on, and rush on, without souls. They have their ego and their will; that is enough to keep them going.”

Go to any mass sporting event for confirmation of this observation.

On a more serious note: Spiritual darkness doesn't kill a person's ability to think and act. A person can move forward and regress at the same time. But as he improves his faculties for thought and action, but doesn't elevate his spiritual nature as well, his capacity–and potential–for doing horrible things increases. Because Society is Man writ large (Plato), the same truth applies to civilization. Eric Voeglin liked to point out that a civilization can progress and regress at the same time.

Art is moral

The essential function of art is moral. Not aesthetic, not decorative, not pastime and recreation. But moral. . . . But a passionate, implicit morality, not didactic. A morality which changes the blood, rather than the mind. Changes the blood first. The mind follows later, in the wake.

“Art,” Maritain said, “is a virtue of the practical intellect.” The artist must possess the virtue proper to his activity. In this, it is aesthetic. Art is concerned with morality, but I think morality is secondary. The artist paints–writes, sculpts . . . conveys–what is true/real. Morality is nothing less than living in accordance with truth.

If an artist sets out to be moral, it's hard to imagine how his art won't be didactic.

You sculpt the piece first. The meaning comes later.

The American greats attacked the old morality?

Hawthorne, Poe, Longfellow, Emerson, Melville: it is the moral issue which engages them. They all feel uneasy about the old morality. Sensuously, passionally, they all attack the old morality. But they know nothing better, mentally. Therefore they give tight mental allegiance to a morality which all their passion goes to destroy. Hence the duplicity which is the fatal flaw in them, most fatal in the most perfect American work of art, The Scarlet Letter.

Really? I'm no Hawthorne expert, but the witness of his daughter Rose implies that he had a mental and emotional allegiance to traditional morality (whether that's the same morality Lawrence is referring to, I don't know). From Flannery O'Connor's The Habit of Being:

You know [St. Rose's Free Home for Incurable Cancer] was founded by Hawthorne's daughter? My evil imagination tells me that this was God's way of rewarding Hawthorne for hating the Transcendentalists. One of my Nashville friends was telling me that Hawthorne couldn't stand Emerson or any of that crowd. When one of them came in the front door, Hawthorne went out the back. He met one of them one morning and snarled, “Good morning Mr. G., how is your oversoul this morning?”