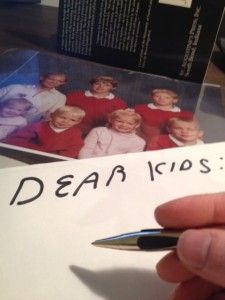

Thursday

Letters to Children

Living in the Present I

The nineteenth-century Scottish fantasy writer, George MacDonald, lived in intense poverty. He wrote fairy tales in order to eke out a living for his family. Yet he had a peaceful mind. Said C.S. Lewis about him: “His peace of mind came not from building on the future but from resting in what he called 'the Holy Present'.”

The Holy Present is a mode of living in which you don't about the past or the future. You think about the job at hand, or the priest's words, or an old tree that you see in a park. You think about the game you're playing with your children, or the conversation you're having with your friend, or the consultation you're having with your customer or client. Or you might just think about God. You don't think about the time that such activities are taking and how you may not have enough time later to get other things done. You also should not think about things that have happened in the past that have no bearing on the present moment.

You should strive to live in the Holy Present because, quite simply, it's how we're meant to live. We have no power over the past and precious little control over the future. Here's how C.S. Lewis described it in The Screwtape Letters: God wants men to attend chiefly to two things: “to eternity itself, and to that point of time which they call the Present. For the Present is the point at which time touches eternity. Of the present moment, and of it only, humans have an experience which (God) has of reality as a whole; in it alone freedom and actuality are offered them.”

If you learn to live in the Holy Present, all sorts of problems fade away. Anxiety vanishes. The idea of not having time for something is foreign. Concern about money fades away. Worry about future events–terrorist attacks, stock market crashes, illnesses–crumbles. Resentment or sorrow over past events never surface.

I'm painfully aware that I'm writing like someone who has attained this state of mind, but as noted at the outset, I haven't. I have, however, tasted this blessed state. You may recall how I loved to get up early on Saturday mornings to sit in my study downstairs and read, and how I'd do the same thing on summer vacations. You may remember days when we would go to an amusement park, or take a leisurely walk and idly point at different things and discuss them, or play at a local playground. You may also recall (looking from your classroom windows) seeing me walking to a weekday morning Mass.

I loved those things–because they were times spent in the Holy Present. When I sat in my study, I only cared about the book in my hand or the subject I was writing about in my hand. Sometimes I just sat there and stared at the wall, maybe looking at one of the icons or crosses. When we spent fun afternoons together, I cared for nothing else but being with you and watching you have fun. When I went to weekday Masses, there was nothing to do but sit listen to the liturgy.

You see, the Holy Present is not just a mystical thing. It is a thing everyone has enjoyed. Every person can tell you about carefree days and how happy they were during such days. But then they sigh and turn themselves to the drudgery and troubles of daily living, as though the two are completely separate.

They got it wrong. The Holy Present works in any setting or on any day, whether it's work or play, just as breathing works in any setting and food is needed regardless of the day's activities.

I realize, of course, there are severe differences between working at the job and playing at an amusement park. But the point is this: the Holy Present goes with both, just as breathing goes with both exercising and sleeping.

Hopefully, you'll experience this with your job. When you have a good project, one you can “sink your teeth into,” you'll find the workday passes quickly and enjoyably, in a manner similar to the way vacation days past quickly and enjoyably.

I've given you some very mundane examples of the Holy Present and they're apt, but the Holy Present can call you to so much more. One writer once called the Holy Present the sacrament of the present moment. By “sacrament,” we understand something that is a means of grace. Grace works at different levels. It can sanctify the most mundane chores (reference the life of St. Therese of Lisieux) or it can raise someone to mystical heights of contemplation.

The same goes for the Holy Present. Most of us will taste its grace in the mundane things of life, but it can lead us to so much more–if we will just cultivate it in all our stations of life. It will bring happiness to our everyday lives; it might take us to great spiritual heights. I have tasted a little bit of these greater heights during (all too) short periods in my life where I've been able to fix myself in the Holy Present, but I always ended up backsliding into worry and other mental poisons, probably because I hadn't even heard of the Holy Present until I was thirty. I hope, by exposing it to you earlier–implicitly through vague counsels and examples in your childhood and explicitly in this letter–you will do better.