Tuesday

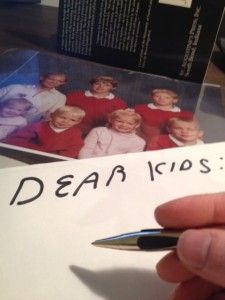

Letters to Children

Unfortunately, we live in a society that tends to look at the intellectual effort in connection with getting a practical education–i.e., an education that allows one to get a job–and with succeeding at the resulting job, as the end-all of intellectual endeavors. In other words, mental effort is viewed as a good thing only when it is spent on the pursuit of money (or the pursuit of fame or power). Other types of mental effort are deemed impractical and a waste of time.

And when the term “practical” is understood narrowly to mean only those pursuits that produce money or power, then all other intellectual pursuits are impractical. I adopt that type of reasoning in my letter on frivolity, listing “philosophizing” as a superfluous activity. It is not undertaken with a set purpose (specifically, for making money), so it is impractical.

But it is interesting to know that the Romans didn't view philosophy as an impractical pursuit. Writing the introduction to a collection of Cicero's essays (On the Good Life), Michael Grant said, “philosophy was regarded as a strictly practical study–something which, if approached in the right way, was perfectly capable of guiding and improving people's lives.”

Philosophy to the Romans was considered practical. And I think the Romans were right, as long as the term “practical” is understood in its large sense. Pursuing practical studies is not just a way to make money and acquire fame and power; it is a way to the good life, a way to learn how to live.

Philosophy, in other words, teaches us how to lead our lives and therefore it is a practical pursuit. It is in this sense that I hope all of you develop practical minds. I don't want you to be practical in the current sense of the term (i.e., concentrated on money and power); I want you practical in the classical sense of the term (i.e., concentrated on living the good life).

If you pursue practicality in this vein, you will quickly find that the “practical” in the narrow, money-focused, sense and “practical” in the larger, good-life focused, sense, overlap to a degree (they do, incidentally, in Cicero's essays), but more often conflict. The pursuit of money is not the end-all of life. You'll find that everyone agrees with this statement in their minds and lips, but in their hearts and pursuits, they act otherwise. They say and know that money can't buy happiness, but then they pursue it zealously for the sake of accumulating it and for the sake of spending it on things that they think make them happy (vacations, cars, nice clothes, etc.). Their whole lives are spent for the sake of money and money-once-removed (i.e., those things money can buy).

You need to avoid this double life. You will need to earn money and be concerned with practicality in its narrow sense, yes. But you need to make sure that you are practical in the larger sense–make sure money rests on the mid-rung of the things of life and stays there. You will need the money, but because it frees you to lead a good life in which you pursue the higher things of life. And you can only know about those higher things if you pursue practical studies in the large sense of the term–specifically, if you pursue philosophy.