(Untitled)

The Weekend Eudemon

So That's the Relevance of Hip Hop!

"I think that the whole future of my race hinges on the question as to whether or not it can make itself of such indispensable value that the people in the town and the state where we reside will feel that our presence is necessary to the happiness and well-being of the community. No man who continues to add something to the material, intellectual, and moral well-being of the place in which he lives is long left without proper reward. This is a great human law which cannot be permanently nullified." Booker T. Washington, Up From Slavery (1901).

Our "headline," by the way, isn't intended as an insult to blacks. But when you read Washington and his noble vision, and then see the degradation of the inner cities and outlets like MTV celebrating the degradation, it calls for some sort of concern, whether in the form of scoffing or otherwise.

We've started reading W.E.B. Du Bois' The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois disliked Washington's vision for black Americans, so maybe there'll be something in the book to soften our view, but we doubt it. We'll keep you posted.

The Early Melvin

Riveting prayer found in Benedict J. Groeschel's Praying to Our Lord Jesus Christ (Ignatius 2004).

"He who suspended the earth is suspended; he who fixed the heavens is fixed; he who fastened all things is fastened to the wood; the Master is outraged; God is murdered." Melito of Sardis, Second Century.

The Lawyers Are Salivating

Just as divorce lawyers salivate at the prospect of gay marriage, it looks like the whole concept of assisted suicide could provide fodder for medical malpractice. From a story at CNN:

"David Prueitt, who had lung cancer, took what was believed to be a fatal dose of a barbiturate prescribed by his doctor in January. He fell into a coma within minutes, but woke up three days later, said his wife Lynda Romig Prueitt.

"Prueitt's wife told The Oregonian newspaper that he asked, 'Why am I not dead?'

"Prueitt, 42, lived for two more weeks before dying of natural causes at his Estacada home, about 35 miles southeast of Portland.

"The state Department of Human Services will turn the case over to the Board of Medical Examiners or state Board of Pharmacy to determine if the procedure or drugs were faulty, said Dr. Katrina Hedberg, assistant state epidemiologist."

The article says such incidents are rare. The legal damages in such cases would also be tough to calculate. Nonetheless, the suits will be coming. They'll be experimental at first, but those are often the best kind for lawyers looking for a novel way to generate fees and publicity.

The Punchy Journal

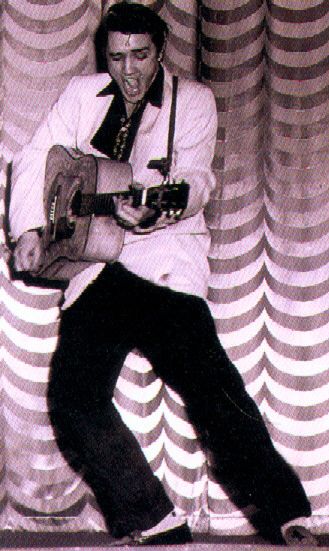

. . . It was also the anniversary date of the release of Elvis's first number one hit, "Heartbreak Hotel," so we talked about Elvis.

All of us are fans. Gotta be. We were in middle school when Elvis died, and every cultural event that happens when you're in middle school gets branded on your brain as significant. Growing up near Detroit, I still think Bill Munson is the greatest back-up quarterback ever to play in the NFL.

I, however, traveled to the Elvis Fan Dome by an odd route.

In college, a friend went to a mega-flea market and bought an Elvis clock: a heavily-varnished piece of wood with a serious black-n-white Elvis picture on the front. We were dyin'; the whole tacky Elvis phenomenon cracked us up. I went to the show and bought one.

After graduation, I hung it up in my abodes as a joke.

A few years later, I visited my brother, who had just moved to Tupelo. I did the Elvis tour: birthplace in Tupelo, drove an hour to Memphis for the Graceland Tour and to Beal Street to see the Elvis statue, and checked out some Elvis sites in Nashville. I bought souvenirs.

When people saw the Elvis clock and other Elvis paraphernalia, they just assumed I was a sincere (even fanatical) fan. When birthdays and Christmas came, I started getting Elvis stuff, including Elvis tapes and CDs. I started listening to them.

And became a fan.

Now, I still don't own a velvet Elvis. I'm not a big enough fan to break-up my marriage over him, and that'd surely happen if I spent $200 on one of those and hung it in the living room.

But I do dig his music, especially his live stuff where he re-made other artists' songs. Somewhat humorous, but very talented overall. He was a great show man.

I've always kinda suspected that Elvis could give a microcosm view of modern life. Not of the worn-out "rags to riches" variety. And not of the fame to drugs and early death variety, either.

Elvis's biography is easy enough to lay out: Born in poverty. One of twins, the other dying at birth. Raised to be good and simple. Grew up to be huge and successful through a talented voice, good looks, and a persona uniquely suited to the growing rock-n-roll movement in America.

It's the image of Colonel Parker, though, that intrigues me. Without Parker, Elvis wouldn't have gotten so big.

But without Parker, Elvis may have gotten bigger. And better.

Parker became Elvis' manager in 1955, when Elvis was twenty. Elvis was a star in the South, but unknown nationally. Parker bought out Elvis' contract with Sun records for $35,000 (big sum back then) and took him to RCA and national fame.

Parker's contract with Elvis gave Parker decision-making authority over nearly every aspect of Elvis's career–primarily for Parker's monetary benefit.

From David Hajdu's "Hustling Elvis," New York Review of Books, October 9, 2003

Parker thought nothing of music or culture of any sort. "He really was tone deaf," the journalist Alanna Nash quotes Joan Deary of RCA Records as saying in The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. . . Parker, like many people in the 1950s (including some of Presley's fans), thought of Elvis as a charismatic novelty–an exotic, unique, and therefore valuable commodity in the entertainment trade. A veteran of the lurid, freewheeling carnivals and tent shows that appeared on the outskirts of rural communities and disappeared with the townsfolk's earnings, the Colonel learned most of what he knew about show business and public taste as a sideshow barker and concessionaire. (He had a special fascination for one exhibit, a man with long hair, a beard, and a phony tail billed as "the Thing! Half Man, Half Animal!" according to Nash.)

[Parker] carried on negotiations with film studios as if he and Presley were collaborators and full partners, and he signed everything, even his Christmas cards, as "Elvis and the Colonel." At the same time, his contract with Presley gave Parker independent decision-making authority over nearly every aspect of Elvis's career, and he rigged the financial machinery so that he, the manager, often made more money than his client. Parker sometimes had Presley sign the bottom of blank contracts, which he would fill in later. Nash recounts an exchange between a British journalist and Parker in 1968. "Is it true that you take fifty percent of everything Elvis earns?" Parker was asked. After a moment's thought, he answered, "No, that's not true at all. He takes fifty percent of everything I earn."

He claimed that he and Presley had a commensurate division of responsibilities: Elvis made the music and the movies, and the Colonel made the deals. The truth was knottier, as it often is with creative artists and their managers. Parker's machinations dictated or limited most of Presley's professional activities–the kinds of songs Presley could record, and when, where, and with what musicians, which movies he could make as well as many of his personal moves, down to the friends he could see, how they would spend their time, and even the woman he would marry. . . "Look, it's pretty easy," Parker told his client. "We do it this way, we make money. We do it your way, we don't make money." Elvis ended up doing almost everything the Colonel's way, frequently to his career's and his own detriment and, in time, to his frustration.

But money's not the only thing he took from Elvis.

Parker stifled the development of Elvis' music and crammed infantile and ridiculous movie parts down his throat, insisting Elvis make only low-budget and formulaic movies that were guaranteed to make at least a small profit (for that's all Parker cared about). He refused to allow Elvis to appear in Thunder Road, West Side Story, or Midnight Cowboy.

Elvis also considered himself a Christian and, like many entertainers, was interested in Eastern religious life, of the ascetic sort. I hear he even considered becoming a monk. Hardly a thing Parker would've encouraged.

Elvis may have been a creative genius. Might he have progressed beyond pop pap to produce some truly memorable music like the Beatles? Might he have become a great actor? Might he have become religious and bring his creativity to a unique prayer life?

Probably none of the above. But they were all possibilities. The seeds were there.

But Parker smoked everything, including the seeds, leaving Elvis with the ashes of pop culture stardom and the drugs that eventually killed him.

The problem with Parker is that he was a mercenary. He killed (Elvis) for money. And Elvis signed on with him because Parker would show him how to make money. . .