The Little Arts

Talk is Not Cheap

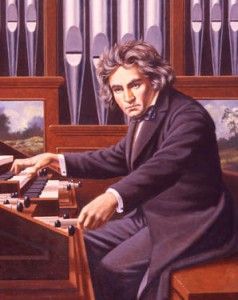

Ludwig van Beethoven once explained to Johann Goethe that the artist is a great man deserves reverence. To illustrate his point, and to Goethe's flabbergasted astonishment, Beethoven crossed his arms and rudely walked through a group of gathered nobility.

Beethoven's impolite walk mirrored his stride through life. He saw himself as one of the great artists, and thus he supposed he deserved everyone's deepest reverence, and that he stood above the everyday conventions of kindness and politeness.

Beethoven was an extremely difficult man. He tyrannized his family to the point of pushing one member to attempt suicide; many doctors refused him as a patient; he abused servants so fearsomely that few would work for him; no woman would marry him. He was the quintessential lonely artistic genius, and has been called the first modern artist because he gave birth to the modern notion that the great artist must be irritable and self-obsessed.

In fairness to him, it must be admitted that much of his crankiness stemmed from his wretched health–colic, diarrhea, fevers, septic abscesses, and the otosclerosis that gradually took away his hearing. But his cranky specter still hovers over modernity's mental landscape. Many people, especially the young, think themselves destined for some sort of greatness–in art, business, sports, politics, or whatever. And, following Beethoven's example, many of them tend to disdain the ordinary things of everyday life, thinking such things must be approached within an eccentric scorn, as though these things were beneath their own looming greatness.

This is distressing. When the mental climate of a physically ill and terribly-unique genius like Beethoven is imitated, then we lose the “little arts” (to use the words of Richard Weaver), like conversation, hospitality, and manners. Conversation is dismissed as small talk; hospitality is dodged whenever possible; all socializing is dismissed as a waste of time. Most significantly, many artists (or imagine themselves artists) forego, even ridicule, these little arts, thinking such things detract from greater pursuits.

This is a wrongheaded notion. A little art like conversation presents an opportunity to create, just like a blank canvass presents an opportunity to create a painting. Good conversation requires skill–the use of an opening line, the use of entertaining information, patience, and (sometimes most importantly) the ability to close a conversation gracefully. Good conversation also requires a fruitful–not to mention a ready–imagination.

But most importantly, good conversation requires concern for the other person, and that first requires the lack of self-regard. And lack of self-regard is the hallmark of the artist. William Blake once observed,

I should be sorry if I had any earthly fame, for whatever natural glory a man has is so much detracted from his spiritual glory. I wish to do nothing for profit. I wish to live for art. I want nothing whatever. I am quite happy.

As Blake testifies, the true artist is detached from himself. Because he tends to be the sort of person who doesn't care too much about himself, he is drawn to realities outside himself. In the words of philosopher Josef Pieper, the artist's is a “purely receptive stance toward reality, undisturbed by any interruption by the will.” This receptive stance leaves the artist free to reality, to bring it together in his mind, then to put it on the canvas, page, or stage, without the distorting refraction of will and ego.

Just like the artist, the good conversationalist must also be detached from himself. The self-obsessed person is a bad conversationalist (anyone who doubts this doesn't get out much) and for good reason: He has no ability to create because he is too self-centered to appreciate the reality outside of himself.

His inability to carry on a conversation will tend to affect his painting and writing. The little arts like conversation develop the capacity to rise above self-regard. If a person is self-absorbed throughout the day, he develops a mental pattern of self-absorption that must be broken before a session of creativity can take place. The other-regarding person, however, is always ready for a session of creativity because his mid has been artistically inclined throughout the day.

For this reason, the good artist is apt to be a good conversationalist. (Even Beethoven laughed and joked with his acquaintances and was often kind, his violent outbursts notwithstanding.) The little art of conversation comes from the same source as painting and writing, so the artist can do both, like the myriad of artists who conquered more than one “big” art, like Blake (poet and painter), Leonardo da Vinci (painter and inventory), T.S. Eliot (poet and essayist), and Michelangelo (poet and painter).

And like Chesterton. It's no coincidence that Chesterton was one of the most prolific writers in English history and an excellent conversationalist. It's no coincidence that his friends and acquaintances consistently testify to his charitable, caring spirit. It's no coincidence that he tended to neglect his personal affairs. Like a true artist, he was rarely focused on himself, with the result that he was a great artist, in the big and in the little. From his poems, to his drawings, to his essays, to his stories, to his friends, to his beer-drinking companionship, art was a steady feature of his life.

Previously published in Gilbert Magazine.