Humility and Vianney, Part 1

Socrates was an ugly, poor man with no pretensions. In the eyes of the world, he was a misfit and fool, a constant butt of jokes around sophisticated Athens, but he didn't mind. He was very humble, thinking little of himself and caring little for his earthly affairs.

His humility was combined with intense wisdom, as evidenced by the spontaneous school of promising young men (like Plato) gathered about him to learn about the higher issues of existence. Socrates became known for his ability to stump Athens' “important” men through what became known as the “Socratic method,” which is popularly assumed to be a browbeating device of intellectuals against students. But Socrates in reality stumped them because his questions permeated the depths of important issues, depths he had plumbed in his quiet and simple life of contemplation.

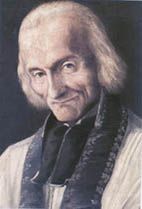

This combination–intense humility and deep wisdom–is not exclusive to Socrates. It has happened many times. Most significantly, it occurred four hundred years after Socrates' execution, when Jesus Christ was born into an intensely humble life, remained a poor and humble man all His life, but possessed unparalleled wisdom. It is also a consistent feature of Christ's best followers, like St. Thomas, one of the most-learned and wise men in history, but a man who always remained humble, and St. Therese of Lisieux, a simple girl who, notwithstanding her lack of higher education, became a doctor of the Church. It is perhaps the most-stunning characteristic of St. John Vianney, the Cure d'Ars.

Vianney was considered dull-witted most of his adult life. When he entered a make-shift seminary at age 19, the other two students (adolsescent boys), giggled at his intellectual inability and grew frustrated when he delayed lessons with his slowness. He couldn't meet the intellectual requirements for becoming a priest, even though the requirements were relaxed at that time in order to alleviate a priest shortage following the Napoleanic Wars. He failed his examinations at major seminary and was asked to leave. Given another chance and a vigorous 3-month tutorial by a learned friend, he failed again. He finally passed, after being allowed to take the exam in special surroundings (a relaxed atmosphere, so he wouldn't get too nervous).

St. John Vianney was very humble. Throughout his life, he never showed any self-regard. As a boy, he worked hard for his father but always made time to pray. As a 19-year-old seminarian, John kneeled at the feet of a 12-year-old fellow student who became exasperated with John. As a new parish priest, he declined the help of the household servant sent to him at his rectory. As pastor, he showed little, if any, regard for his own well-being. He prayed constantly for the salvation of the souls in his parish. He routinely listened to confessions for over eight hours a day. He left his parish only twice during his 29-year stint as pastor of Ars, and spent one of the stints caring for the souls of hundreds of pilgrims who found him as he tried to take a brief, well-merited, break from his duties.

His humility crafted a simple but penetrating wisdom. This was apparent even in his early years at the seminary, when, although he couldn't articulate the lessons well, his application of the lessons was superb. As Pastor at Ars, his constant teaching (he is known as the man who out-talked the Devil) converted a spiritually-moribund village into a sphere of piety. Today, he is widely quoted–his words are fetched by priests hoping to give insight to parishioners and assembled by publishers hoping to sell wisdom.

He was able to pass along truths in words that the simplest person can understand–strong evidence of deep understanding. He did not need a lengthy exegesis to explain the philosophy of death and justice (embodied in the Greek word Thanatos). He merely told listeners, “To die well we must live well.” He did not need to understand psychology to explain that the “way to destroy bad habits is by watchfulness and by doing often those things which are the opposite to one's besetting sins.” He did not need to study and read the Stoics, Plato and Aristotle to understand the oneness of virtue: “It is only the first step which is hard in the way of abnegation. When we are once fairly entered upon it, all goes smoothly; and when we have this virtue, we have every other.” He understood the principal of connaturality so well that he could summarize it for his rowdy parishioners as “It is just those who have the least fear of God and his judgments in their hearts that have nothing but pleasure in their heads.” The examples of wisdom obtain by this intensely humble saint could go on and on.