BYCU: Essay Edition

The Joy of Drinking

St. George he was for England,

And before he killed the dragon

He drank a pint of English ale

Out of an English flagon.

For though he fast readily

In hair-shirt or in mail,

It isn't safe to give him cakes

Unless you give him ale.

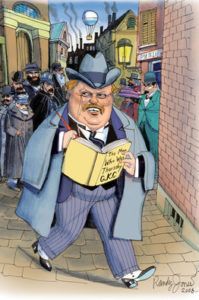

So rhymed Chesterton, a reverent man with a deep and sure religious sense. So rhymed Chesterton about St. George, patron saint of Chesterton's beloved England. As this poem suggests, Chesterton saw no inconsistency in St. George's saint status and his taste for beer. This isn't surprising because Chesterton saw no inconsistency in his own love for Christ and his taste for beer.

Many people cannot appreciate Chesterton's poem because they cannot reconcile Chesterton's taste for drink and his religious sense. Verse that celebrates a religious figure's beer drinking would strike them as disrespectful or absurd. They would, spurred on by today's anti-drinking slogans, dismiss the poem as an antiquated product of an optimistic view of drinking that is impossible in today's world of drunk driving fatalities and teenage drinking.

Today's anti-drinking campaign is creating an increasing polarization between drinkers and non-drinkers. The next time you attend a social function, observe the non-drinkers when a big-grinned man reaches for another beer. You will see at least one or two individuals give him a crooked smile, dig into him with a churlish comment, or give a knowing glance to their spouses indicating it's time to leave.

This polarization is unfortunate. It regulates drinking to the bad elements of society, thus depriving good people of the joys of good drinking--joys that, properly understood, highlight the chrism of existence. Good drinking is marked by a feeling of rejoicing: it is never an attempt to escape from trouble. As Chesterton said: “Drink because you are happy, but never because you are miserable. Never drink when you are wretched without it, or you will be like the grey-faced gin-drinker in the slum.”

Good drinking is not a flight from reality--the good drinker is acutely aware of the realities surrounding him. Indeed, this awareness is the key to understanding good drinking. Although there are periodic exceptions, life is generally good because earthly existence is a gift of God. This fact is clouded by the grinding troubles of everyday life. But most of these troubles are not troubles at all--they are merely worries stemming from ambitions, ambitions triggered by the self's pursuit of gratification, a pursuit that causes us to feel harried throughout the workday, to struggle to earn more money than we really need, to dwell on petty things that are beneath our status as creatures made in God's image.

The good drinker drinks in order to see through the ambition and pettiness. As his drink works through his system, he slowly lets go of his self-obsessiveness and accompanying worries, with the result that he decreasingly sees existence through the distorting prism of self-regard. As the prism breaks apart, he becomes re-acquainted with the fact that earthly life is a blessed gift.

The good drinker often continues to drink in order to remove any shred of the self-regard that clouds his ability to see the gift of existence. He drinks more, and becomes less concerned about what others think about him. He drinks more, and becomes desirous of company. He drinks more, and becomes increasingly good natured. (Contrast this with the tight-faced teetotaler.)

After enough drinks, everything seems good. Rather, everything is good, and the drinker becomes acutely aware of this. This awareness gives him a joy that he has difficulty finding in the everyday world as he struggles with an assortment of obligations, moral and otherwise, that tend to push him toward self-regarding concerns. The self-regarding concerns are shoved to the background and treated like the nonentities that--in the most real, theological sense possible--they are.

But after this stage, it is easy to slop into bad drinking. With a few drinks, the good drinker enters a joy that he wants to retain and increase, so he drinks more. This is a problem. Joy is a spiritual trait that cannot be attained solely through material means. Any person who attempts to grab joy through excessive drink tries to take command of a spiritual trait through earthly means, like a black magician who tries to gain the supernatural through strictly natural means and is willing, in the words of Thomas Howard, to rip the “fabric of things: obscenities, outrages, and perversions in his wrongheaded quest for supernatural joy through mundane excess."

But the good drinker is no black magician. The black magician, like the teetotaler who doesn't drink because it's beneath him, is obsessed with himself. Not so the good drinker. He drinks because it helps him put aside his feeling of self-importance--the raging falsity that catalyzes ruinous ambition and triggers every worry.

And as his self-importance shrinks, his feeling of rejoicing expands. These episodes of rejoicing then better dispose the drinker to give thanks always, regardless of drink. Under the influence of drink, he will pray with laughter. Later, in intense sobriety, he will pray with a stream of joy that has recently been replenished.

St. George he is for England,

And shall wear the shield he wore

When we go out in armor

With the battle-cross before.

But though he is jolly company

And very pleased to dine,

It isn't safe to give him nuts

Unless you give him wine.

Previously published in Gilbert Magazine. I kept the copyright, and to the best of my knowledge, it's not available anywhere on the Web.