Thursday

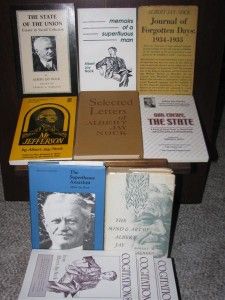

Nock Notions

"To be ignorant of one's ignorance is the malady of the ignorant."

Nock starts Memoirs of a Superfluous Man with that quote from Amos Bronson Alcott. He no doubt loved it, as do I.

But I doubt Nock and I would apply it the same way. To me, we are all ignorant, including me. To Nock, most people are ignorant, but not him. I give myself an intellectual leg up on the average man because I'm aware that I don't have a leg up. Nock, conversely, gives himself a leg up on the average man because, well, he is above the average man.

I dig Nock. A lot. But this snobbishness in his character and thought can't be denied. Indeed, he wouldn't deny it.

On what did he base this snobbishness? I think it's fair to say that he'd base it one thing and one thing only: his classical education. He was educated in Greek and Latin, back in the days before we invented the fiction that everyone was educable, just as long as we discarded those thing that make people educated, like Greek and Latin.

Nock absorbed the classics . . . in Latin and Greek. Although he allowed for some good translations, he held that a true education in the classics must come from reading the classics: in the original language. Too much, he thought, was lost in translation.

He firmly held that a classical education allowed a person to see things as they really are, which gives a person an inestimable advantage over the run-of-the-mill fellow who is fodder for propaganda and passion.

I doubt Nock would have enjoyed discourse with me. I am, you see, a product of the Dewey education system and I am, therefore, an idiot, in the Nockian universe. My only saving grace in things intellectual is that everyone around me--my friends, my clients, the politicians who lord over me--are likewise Nockian idiots.

Oddly, I'm not remotely offended by Nock's position. Indeed, I incline towards it. Classical thought ran for thousands of years. It encountered the best to be thought and all the tests to be fought. If a person reads the classics--Thucydides, Sophocles, Plato--one gets a lifetime of learning before one turns 22. It's almost like he gets to mature twice, which would give a person an advantage and allow him to make more of life "the second time around," so to speak.

If a person seeks a similar advantage these days, where does he turn? It's too late for me to obtain a classical education, incidentally. I'm 45. I feel blessed if I can just absorb the classically-educated attitude via osmosis through Nock: I shook the hand of the man who shook the hand of Babe Ruth.

It's not temporally too late for my children, but it's culturally too late. They're not going to learn Greek or Latin from me, and they're sure not going to get it at the local public high school (the Alcott test cases will assure it).

So what's an ignoramus to do?

I think the answer is found in Catholic spirituality, oddly enough. And for this reason, not only is it not too late for me, it's also not too late for my children.

Nock hammers on about his objectivity repeatedly. He, for instance, writes that, when some matter of public affairs would catch his attention, "I would 'see it as it was,' more or less by a kind of reflex;--the Platonist habit of looking for 'the reason of the thing' had become almost automatic." Chp. 7. For Nock, this ability to "see things as they are" is the most important mark of the educated man. He uses the phrase no fewer than three times in Memoirs.

You know who else sees things as they are?

Saints.

Our culture has taught us that saints are eccentric folks, too lofty in mind to do anything practical.

Our culture is stupid. Saints have traditionally been very practical, and they've often made great administrators. Through a life of holiness, a person shrinks the self, his ego, leaving himself in a great position to see things as they really are. The ego, after all, is easily the most-distorting element in a person. When a person sees things through self-interest (or passion, or emotion, or greed, or what have you), he can't help but distort the results.

The saint, by shrinking the self, sees things as they really are. It's the saint who can join Nock's claim that, like Plato, they can see things as they really are.

The big difference, though, is the saint wouldn't tell anybody about it.